When musicians play together, we always try to be “in sync,” unless, of course, we are playing Steve Reich’s Piano Phase or Violin Phase. And then we find how difficult it is, when two musicians are playing the same music, to be purposefully “out of sync” or out of phase. So are we hardwired to want to play “in sync?” What is happening in our brains when we are performing together? First, a necessary “sidebar” to talk about brainwaves.

100 billion used to be the figure that was always given for the number of brain cells, or neurons, in the human brain. But we seem to have lost about 14 billion. Although you still see the higher figure, more recent research shows that there are actually 86 billion neurons in our brain, which is still an inconceivable number. (You may not want to know that researchers determined this figure by making soup out of brains that had been donated to science. Check out the story here.)

Those 86 billion neurons use electricity to communicate our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, and when millions of neurons are sending signals at the same time, a significant amount of electricity is produced in the brain. That electricity can be measured by EEG, or electroencephalography. One of the primary uses of EEG is to diagnose epilepsy, and it is also used to diagnose sleep disorders and coma. And, with very interesting results, It has also been used in studies concerning the brains of musicians.

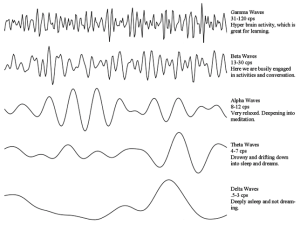

When the electrical impulses from millions of neurons sync together, they form brainwaves. Brainwaves are divided into bandwidths, with each range representative of a different function. But in reality, they are all on a continuum.

In the image on the right, delta waves, the slowest, are indicative of deep sleep. Theta waves occur in sleep but also in deep meditation. Alpha waves are present when you are awake but not processing much information. Beta waves are dominant in our normal waking state and are associated with being engaged, with decision making, cognitive tasks, and focused mental activity. Gamma waves, the fastest, are the most recently discovered, and are related to associative learning, the formation of ideas, and memory processing.

In 2009, scientists at the Max Planck Institute in Berlin found that when two guitarists played together, their brain waves synchronized. The researchers recorded the electrical activity of the brain – through EEG – in eight pairs of guitarists. Each pair played in unison a short jazz-fusion melody up to 60 times while their brain waves were being measured.

The similarities in the brain wave patterns in each pair of guitarists increased significantly – first when they listened to the beat of a metronome in preparation for playing and then again when they began to play together. And these were guitarists who had never played together previously. The duos were assigned as part of the study.

What I find most fascinating about this study is that the brain waves the researchers measured are in the theta and delta frequency bands. These low frequency waves have been found in other research to be implicated in social interactions, in shared tasks, and in motor functions. But they are also the frequency bands associated with drowsiness and sleep – our unconscious brain. So what does that mean?

After completing the study and looking at the results, the researchers wondered if perhaps the brains of the two guitarists synchronized because they were playing the same melody in unison and were using similar motor patterns, or if something else was going on. So another study was conducted, but this time the guitarists played two different parts.

32 guitarists participated, forming 16 pairs. The guitarists were all experienced, with an average of 23 years of playing. Several were currently playing in an ensemble, ten had studied or were studying at a conservatory. The pairs of guitarists played a rondo sequence from a Sonata in D Major by Christian Gottlieb Schiedler. Originally for violin and guitar, the segment used was rearranged to give the two guitarists different, but fairly equal parts. The researchers assigned roles of leader and follower in each of the pairs, the leader giving the cues. They wanted to see if having a clear leader and follower affected the synchronization patterns.

And it did. The researchers looked at the brain wave patterns both within each individual and also between the two players. When they looked at the synchronization of brain waves within the leader’s brain, they found that synchronization of his brain waves had already begun before playing began. They speculated that could be a reflection of his decision to begin playing.

And when the researchers looked at the coherence of the signals between the two musicians, the results were remarkable. They found very strong synchronization of brain waves, particularly at the points where the leader was giving cues. In this study, as in the first one, they looked at theta and delta frequency bands. These are not the frequencies associated with conscious thought. The guitarists may have been thinking about being in sync and playing together, but the synchronicity shows up at the unconscious level in the brain, not the conscious level.

Scientists are always extremely cautious about reading too much into a study or area of research. But as a performing pianist, I find this particular research about brain waves to be rather awe-inspiring.

Some of us play in established ensembles, performing with the same musicians frequently and therefore we develop a certain rapport. And all of us, at some time or another, are performing with someone for the first time. We meet and spend time rehearsing; we discuss the music and sometimes the composer’s intentions; we talk about phrasing, dynamics, tempos; we try different interpretations, and we spend extra time rehearsing the tricky parts. But we do all of this on a conscious, cognitive level.

It seems almost magical to me that our brains are synchronizing with other musicians at a frequency or wave length that is below the level of consciousness. And our brains are synchronizing even with musicians whom we have just met and are playing with for the first time.

Several months ago, I wrote about research that suggests we may be hardwired to make music. Some of that research deals with babies and infants who seem to have innate musical abilities; other studies look at brain-damaged individuals who retain the ability to make music even if parts of their brains are damaged.

No one involved in the brain wave studies from the Max Planck Institute has suggested the possibility that their studies have anything to do with hardwiring of the brain. But I wonder. It seems to me that this ability of our brains to sync with other musicians with whom we are making music is reason enough to think that making music together is something we are hardwired to do.

****

PS If anyone is interested in reading the research articles, I’m always happy to post the citations. Just let me know.

2 responses to “Making music together syncs brains”

Yes! I wonder what happens in a good choral group. Or, does the EEG of a singer change when he/she begins to think about the piece or mentally rehearse it? Fascinating stuff.

Hi Loren, So far, they have only looked at duos, but would be interesting if they ever studied brain waves in a larger group.