A few years ago one of my students, who usually played with a great deal of musicality, found herself struggling with a Chopin Mazurka that just didn’t seem to “click.” All of the notes and rhythms were there, but it sounded stodgy – not at all like a dance. One day, I suggested that we actually dance to the music. I hadn’t known until I made the suggestion that she had studied ballet for years and dancing was second nature to her. I don’t remember if, that first time, we sang the melody, I played the Mazurka for her to dance to, or if I used a recording, because we eventually did all three. But you know the ending of this story because many of you have had the same experience. It was easier for her to feel the rhythm when she was dancing, and once she had experienced feeling the rhythm of the Mazurka in her body, and her brain had connected body movement to the music, she had no difficulty transferring that same sense of rhythm to the keyboard.

Some of us dance to the music we are learning, we draw, visualize, make up stories, and we teach our students to do the same. We know that approaching the music in a variety of ways helps in the learning process, but we don’t really know why. Let’s look at an intriguing study.

Eckart Altenmüller is the Head of the Department of Music-Physiology and Musician’s Medicine at the University for Music and Theater in Hannover, Germany. In his research, he explores how the brain processes music and also studies motor learning in musicians. Because he is also a well-respected flutist, he knows what it is like to have learned an instrument to the level of being able to perform professionally, something with which most researchers have no personal experience.

In the mid 1990s, Altenmüller and colleague Wilfried Gruhn from Freiburg, Germany, conducted a study to see whether different methods of teaching a musical idea would activate different parts of the brain in the learner. Their subjects were a group of junior high school students, age 13 to 14, all of whom had a comparable background in music. During the study the students were going to learn to distinguish between antecedent and consequent phrases (sometimes called question and answer phrases, the question being a segment of music that doesn’t seem to complete a musical thought and the answer the completion of the thought– like the ending of a song).

Before the actual learning part of the study began, all of the students were given a baseline test in which they were asked to listen to sixty short melodies. They weren’t given any formal rules, just told that the melodies were in a two-part structure and they should determine whether both halves sounded balanced – whether the second seemed to “close” the first. While listening, brain activation patterns were recorded for each subject. After this initial part of the study, the subjects were divided into three groups.

The first group was called the declarative or verbal learner group. They were taught about antecedent and consequent phrases in a traditional way, with verbal explanations, visual aids, looking at the notation. Musical examples were played, but all of the information was given to the students; they never sang or performed themselves.

The second group was the procedural learner group. They were given no verbal explanation, but learned through singing and playing, experimenting to create melodic or rhythmic patterns that would feel as though they completed an initial given pattern. They were shown paintings and artwork to explore balance, and were eventually led through a process of applying what they had learned to musical phrases, actually feeling and hearing the difference between antecedent and consequent phrases, so that they were internalizing what these phrases sound like.

A third group was a control group and they received no instruction.

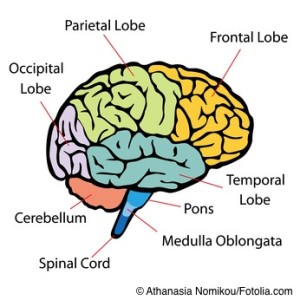

In the pre-test in which all of the students had listened to sixty melodies, all three groups scored virtually the same in their responses to which excerpts had balanced phrases. Brain wave patterns of all subjects while listening to the melodies were the same – some activity in  both the right and left frontal and temporal lobes and in the left parietal lobe. (Last week’s image repeated here.)

both the right and left frontal and temporal lobes and in the left parietal lobe. (Last week’s image repeated here.)

After the learning part of the test, the control group showed no change. The two learning groups, however, had both improved and their scores had improved by about the same amount. But here comes the interesting part. After the learning phase, the first group showed increased activity in the left frontal and temporal regions, which the authors say “may reflect inner speech and analytical step-by-step processing.” The second procedural group showed increased activation of the right frontal lobe and parietal and occipital lobes in both hemispheres, which the authors attribute to “a more global way of processing and to visual-spatial associations.”

When the students were retested a year later, the students in the verbal group showed decreased test scores – they had forgotten much of what they had learned. The scores of the procedural group, on the other hand, remained about the same. They had retained the information, and this group still remembered many of the details about antecedent and consequent phrases. In other words, they had encoded information about antecedent and consequent phrases in a more permanent way.

So teaching the same musical concept in different ways causes different musical representations of that concept in the brain. Antecedent and consequent phrases were represented in different areas of the brain depending on whether the students had learned about them verbally, or whether they had experienced playing and singing them. Being able to label these phrases is quite different from, and not nearly as useful to performance as internalizing what these phrases sound like.

Scientists are always extremely cautious about reading too much into one study. But this one seems rather straightforward. We know that the more ways learning is encoded in the brain, the more likely we are to remember it. So why wouldn’t we want to activate as many brain areas as possible in learning music? To create as many neural pathways as possible? To use both hemispheres as much as possible – since music is processed in both? Granted, playing an instrument is already a hands-on activity. We can’t learn without actually doing it. But why not activate additional brain areas other than those we normally use in the learning process to encode learning in multiple ways – making the learning, and memory, more secure.

My dancer student benefitted from actually dancing the music and feeling it in her body. That experience encoded the Mazurka in a different part of her brain than did playing it. For a pianist, singing all of the voices of a piece would encode learning in different areas of the brain than just playing, and I understand that Nadia Boulanger often required her students who were working on Bach fugues to be able to sing all of the voices from memory. Drawing a visual representation would activate other brain areas. In my second post, Patterns in the Brain, I mentioned a website by Melissa Colgin and Rebecca Shockley that explains the use of graphic representations of the music to aid mental recall – activating different brain circuits and encoding information about music visually. That website is now online and can be found at http://www.memorymapformusic.org

6 responses to “Dance, sing, draw”

Thanks for this terrific post. It gets at something I’ve long believed, that music is, in part, physical gesture translated into sound. My feeling is that if you get too caught up in ink on paper, you can loose that physical, gestural component to the music that creates and conveys emotions on a non-conscious level.

Also, now that you’ve made the point, it seems obvious that using the physical component in teaching would deepen the learning, just as it deepens the experience in the first place.

(something I hope you’ll get to sometime would be mirror neurons – as they seem to have a lot to do with how the gestural component of music, with its emotional content, is conveyed to an audience)

Thanks, Lyle. When I was a student, I heard a masterclass (no longer remember who) in which the master teacher talked about memorizing the “choreography” of the piece. I didn’t really understand the comment at the time, but it became clear as I began to understand that, as you say, “music is, in part, physical gesture translated into sound.” Good topic for longer discussion at some point. As is mirror neurons – a favorite topic of mine. I’ve written about them, spoken to various music groups about them, and am convinced that understanding them is key to learning and performance. So mirror neurons will be coming at some point.

I’m sure this is true. For me, singing while I operated was very soothing at times. I started that while in my training years, and the OR nurses called me ‘the singing senior’. I had one scrub nurse who was extraordinarily good, and she had a magnificent mezzo voice. When we were closing the head, she would load a bunch of needles on their needle drivers, come down off the stand, and do all the tying for me. We would sing duets a lot – a little opera, old hymns, some popular stuff. It was very tension-relieving. And, it made the routine stuff go more quickly!

I know about surgeons playing music in the OR, but I never heard of one actually singing!

I just discovered your blog after seeing an advertisement in Clavier Companion. I’m hooked! I became interested in cognitive psychology and its implications for music during grad school while putting together a presentation on teaching students to memorize music for my degree’s capstone project. I wanted to start from the theory of how people actually memorize and draw practical applications for piano teachers to use. While I was in the research phase, one of my professors introduced me to Shockley’s mapping book. After exploring her ideas, I quickly realized that everything is her book is 100% supported by memory theory research. I also arrived at the conclusion that even playing with the score is a type of memorization: you have to memorize a series of complex, coordinated motions to produce sound. The score is just a set of visual retrieval cues. As you move toward playing without the score, the retrieval cues become aural – you respond to the sounds you hear and your analytical understanding of the piece. This realization completely turned my teaching upside down! Now that I’m not in a university setting and no longer able to access the research journals, I’ll be fascinated to read your blog and see what else will change in my teaching.

Thanks so much for your comments. I’m happy that you found the blog. Becky Shockley’s mapping book is wonderful. It all makes SO much sense – and it’s a perfect example of a musician putting research theory into practice – which is what I am trying to do with the blog. And I think you are right about using the score still being a type of memorization. You have had to memorize sometimes complicated rhythmic, melodic and movement patterns in order to produce the sound. I will be posting something about memory probably during the summer – but there are some researchers who speak about learning and memory as being two sides of the same coin – a concept that certainly makes sense to me. I’ll look forward to hearing from you again.