I saw the film Florence Foster Jenkins a few days ago and haven’t been able to get it out of my mind. I’ve known about Florence since I was a student. She was the stuff of legend, known as the world’s worst singer – with no sense of pitch, no vibrato, frequent register breaks,  glottal stops, and unintelligible diction. Certainly good for a laugh on late nights over a beer when someone had access to an old recording. (Actually, I don’t think her recordings have ever been totally out of print; there have always been reissues of various kinds.)

glottal stops, and unintelligible diction. Certainly good for a laugh on late nights over a beer when someone had access to an old recording. (Actually, I don’t think her recordings have ever been totally out of print; there have always been reissues of various kinds.)

The film, starring Meryl Streep and Hugh Grant, with Simon Helberg as the pianist, is based on the true story of Jenkins, a 1940s New York socialite and generous patron of the arts. Florence desperately wanted to perform the music that she felt so passionate about. And perform she did – with all her deluded fantasies about her abilities. As I watched the film, I felt tugged in two directions: one part of me wanted to laugh at how terrible she sounds, and yet, her joy in performing, her belief in herself, her charm and her clear love of the music made me admire her and realize just how deep her passion for music was.

And nearly everyone has a compulsion for music – either to listen to music or to be involved in making music in some way. Steven Mithen, archaeologist at the University of Reading in the UK and author of The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind, and Body, says that, not only were food and sex necessary to survival for our Stone Age ancestors, but so was music and that is why we have inherited our compulsion to be involved in music. (I’ve written about this previously in Are we hardwired for music?)

If you look around you, this compulsion for music isn’t hard to see (or hear). When I walk on my local rail trail, most other walkers, bicyclists or joggers I encounter are listening to music. I often hear car radios or sound systems when I am driving or walking. Many high school or college students form rock bands as well as sing or play in their school’s ensembles; adults sing in church or community choirs or play in community bands or orchestras.

People write books about their musical journeys: psychologist Gary Marcus in Guitar Zero: The Science of Becoming Musical at Any Age relates his  story of learning to play the guitar as he was turning 40. Noah Adams, correspondent for National Public Radio, chronicles his 52nd year as he learned to play the piano in order to play a favorite piece of music for his wife for Christmas in Piano Lessons: Music, Love, and True Adventures.

story of learning to play the guitar as he was turning 40. Noah Adams, correspondent for National Public Radio, chronicles his 52nd year as he learned to play the piano in order to play a favorite piece of music for his wife for Christmas in Piano Lessons: Music, Love, and True Adventures.

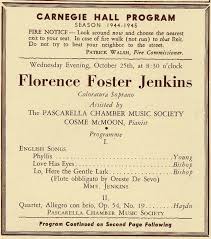

OK, none of these people booked themselves a recital in Carnegie Hall, as Florence did. But when she observed that “Music has been, and is, my life. Music matters,” she meant it. It’s difficult to tell from available accounts, but she apparently played the piano quite well as a child, performing at the White House when Rutherford B. Hayes was president. I don’t think that would have happened had she not had considerable musical ability. But whatever talent she had as a pianist obviously didn’t translate to voice.

She was an unflagging supporter of the arts in New York. But after years of giving her money to the arts, she wanted more – she wanted to give her love of music itself. She decided to realize her ambition to be a performer, and she began giving private voice recitals when she was in her forties (after having had voice lessons for many years). For whatever reason, she was unable to hear her voice the way others heard it. In her mind, her sound was beautiful and her technique flawless, and her primary passion was to share her love of music with audiences and to have them love the music as much as she did.

In the book on which the film was based, Florence Foster Jenkins: The Inspiring True Story of the World’s Worst Singer, Nicholas Martin and Jasper Rees suggest that Jenkins’ musical problems, her inability to hear herself, to be unable to sing in tune, may have been attributable to the toxic side effects of mercury and arsenic, the remedies at the time for syphilis, which she had contracted from her first husband. I haven’t found anything to confirm that idea, but now that the film has attracted so much attention, perhaps someone will research that suggestion further.

But whatever her musical problems, in her great innocence, self-assurance, and bravado, Florence, at least as played by Meryl Streep in the film, absolutely lights up the stage, as from all accounts she did in real life. Her compulsion to make music, aided by her money and her fiercely loyal and loving husband, St. Clair Bayfield, eventually led her to make recordings and to a performance in Carnegie Hall – and made her a laughingstock in New York. While the film is considered a comedy, I found it heartbreaking that someone who wanted so desperately to make music became fodder for ridicule – not only in her own lifetime but in the decades following.

Many of us have worked with students who have a tremendous passion for singing or playing an instrument, but in spite of hours of practice, they just don’t get a lot better. Basic rhythms escape them, they don’t hear if they are out of tune or playing wrong notes, they are missing that indefinable quality we call musicality. Anyone who teaches an instrument or voice has had the experience of having to kindly tell a student that perhaps they should try something else.

And yet – many of them, in spite of being musically challenged, somehow have a need to continue making music at whatever level they are able. How should we be answering that? Yes, they aren’t going to make it as a professional, but isn’t there a place in the world for someone like Florence – who just loves music – to be able to make music in her own fashion? We’re not all great playwrights, novelists or poets, but yet we are all able to communicate something via language.

No doubt Florence should have stuck to singing for supportive friends rather than making recordings and performing in Carnegie Hall, which left her open to such ridicule. And yet the arc of her life has inspired several plays, movies, books and a documentary. Her performances have been available on You Tube for years, and her recordings are still available and continue to be reissued. People may buy them to scoff at how terrible she sounds, but somehow her indomitable spirit, her likability, and her absolute passion for the music she was singing touches something in all of us.

No doubt Florence should have stuck to singing for supportive friends rather than making recordings and performing in Carnegie Hall, which left her open to such ridicule. And yet the arc of her life has inspired several plays, movies, books and a documentary. Her performances have been available on You Tube for years, and her recordings are still available and continue to be reissued. People may buy them to scoff at how terrible she sounds, but somehow her indomitable spirit, her likability, and her absolute passion for the music she was singing touches something in all of us.

Towards the end of her life, she observed that “People may say I can’t sing, but no one can ever say I didn’t sing.” She worked hard to do what she loved – and did it on her own terms. You just have to admire that kind of spirit!

♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪

Next time – a totally different look at the compulsion to make music.

8 responses to “Compulsion for music – part I”

When I read reviews of this movie by non-musicians, it was clear that they did not understand the desire to make music, nor the value of a support network to insure that it happens. It is a touching movie, well-acted, with the surprise of Simon Helberg’s beautiful playing.

Thanks, Kay! The more I delve into her story, the more remarkable I think it is.

I’m conflicted about whether to see this movie (though I adore Meryl Streep). A large part of my stage fright experience is, What are they thinking? They must hear how awful I am! Perhaps even worse, I worry that what I’m hearing or think I’m playing, may not in fact be at all what others are experiencing. What if I sound really awful and don’t recognize it??

I’m simply a passionate amateur, who mostly plays privately. But recently my piano technician made an innocent remark that came as a bolt of lightening– a paradigm shift in my head: “The world doesn’t need more concert pianists. What the world needs is more satisfied amateurs.” And that’s it! I’m not playing Carnegie Hall, people aren’t flocking to my door. But I do have some skills, and I may have something musical to say at my own level. Music is an indescribably important part of my life; even though I’m not a Horowitz or a Liszt, I would be bereft as a person without it.

Thanks, Cindy! What a great comment by your piano technician and wonderful that it caused a paradigm shift for you. As I think about students I have had over the years – some of the most musical with the most to say didn’t have the kind of technique that would lead them to a professional career, but they certainly were able to communicate. So many people would be bereft without music – maybe we all have to find the kind of musical expression that works for us.

I have yet to see the movie but plan to soon. There is so much I am curious about already. I wonder if the compulsion to make music and – particularly to sing- is not just something that we are “pre”-wired to feel compelled toward but something that we become addicted to as a result of the relief and satisfaction that we get from doing it. A chemical release to the brain and back to the body as a result of the physical and emotional stimulation of expressive music making.

My personal experience taught me, when fully invested in this kind of music making, that the anxiety of performing often dissipated. The energy normally spent in inefficient, un-productive ways- combatting what others might think or what I even thought of my own performance- was re-directed toward understanding the music and implementing whatever tools I had in order to communicate an essential and urgent idea. This expressive experience brought both a direct and in-direct reward through an understanding of my own experiences and through the shared, mutually expressive experience I may have had with an audience.

This kind of cognitive, emotional and empathetic experience is in large part, what makes us unique as human. It is at the core of why I am a musician and why I teach music to others.

I’m looking forward to the film and to reading more of all your posts!

Hi Andrea,

Wonderful to see you recently in Glasgow and thanks for these comments. You’ve packed too much into your comments to answer briefly so may lead to another post. But yes, I think emotional feedback probably keeps us making music – whether amateurs or professionals. I’ve known many people (myself included) who say that making music is just something they have to do. But part of that ties into communication, a way to communicate something that you can’t say in words. Large subject. Let’s talk.

My hope is that as music therapy grows as a field, music study won’t be an either/or thing – that if someone loves making music there will be lots of alternatives to chair auditions. I read Swafford’s biography of Charles Ives this summer, and Charles and his dad loved naive players who weren’t technically proficient, but played with a lot of inspiration, which for the Iveses meant a lot. Swafford says that for Ives, music wasn’t something that happens, but the WAY something happens – that there’s music beyond the sounds.

Hi Lyle, Good to hear from you. It’s been a while since I read Swafford, but that’s a very interesting comment – that music is the WAY something happens – music beyond the sounds. Rather seems like John Cage.