In music we often talk about auditory, visual, and motor memory. But outside of the music world, we encounter a dizzying array of memory terms. We read about short-term vs. long-term, explicit vs. implicit, declarative vs. procedural, semantic vs. episodic – and more. So what do all of these terms mean in relationship to memory for music?

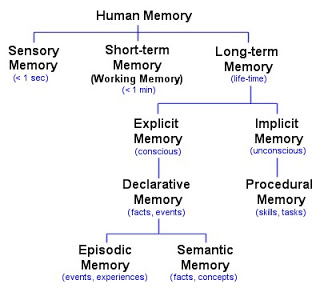

The diagram below, by Luke Mastin, is helpful in sorting out all of the different kinds of memory. All information enters the brain through our senses – or sensory memory. When we are learning a piece, we take in visual, auditory, tactile, and proprioceptive information.

We see the notes, hear what they sound like, feel the pattern on the keys, and feel where our body is in space as we are playing those notes. The brain immediately (less than a second) sends what is pertinent to short-term memory (STM) – sometimes called working memory. And what is pertinent? Only the info we need for the music-reading task at hand – not any extraneous markings that may be on the well-used score you are reading from, and not any background sounds that may be apparent. Rather amazing, actually!

Some scientists don’t consider sensory memory a separate category – they consider it part of STM. You know about the brain’s ability to hold 7 (+ or – 2) pieces of information in STM, and it typically holds it for 10 – 15 seconds – long enough to punch in a telephone number you have just looked up or to remember the beginning of this sentence long enough to relate it to the end of the sentence.

Short-term memory is crucial for sight reading. As we read the score, we store short segments of music in STM so that we can play them as we look ahead at the next segment of music. So our short-term memory is always holding a few notes ahead of what we are actually playing.

The capacity of short-term memory can be increased by chunking individual pieces of information into larger patterns, basically recoding the information in the brain. For example, the 8 digits in the number 10021938 are near the outer limit of what the brain can hold in STM. But if we think of that number in 3 chunks – month, day, year (10-02-1938), rather than 8 digits, it now becomes easier to remember all 8 digits, plus it frees up STM space for more numbers. Or C, E, G, B-flat could be thought of as one chunk, a dominant 7th chord on C, rather than four individual pitches, thus leaving room for 5 or 6 additional chunks of information in STM.

Chunking is based on prior knowledge. You would have to know that dates can be expressed as 2 + 2 + 4 digits to chunk 8 digits as a date, and you would have to have some knowledge of music theory to know that C,E,G, B-flat can be seen as a dominant 7th chord. So the more knowledge we have of a subject, the more readily we will be able to chunk, which is why people who sight-read all the time are so good at it – because they are used to seeing patterns and chunking musical information.

Short-term memory disappears unless we make an effort to transfer it to long-term memory, which is what we do when we learn/memorize a piece of music; we are encoding the information into long-term memory. And we do this in a variety of ways: through repetition, through identifying patterns and relationships, by connecting factual details with the music, by giving the music meaning or associations, and perhaps most important, by being motivated to move the information to long-term memory.

All memory other than short-term comes under the category of long-term memory. LTM is divided into two kinds: explicit and implicit. Explicit memory is memory for facts and events. It is memory that can be consciously recalled, like what you had for breakfast this morning, or memory for a specific piece of music. Explicit memory is sometimes called declarative memory because it is something you can declare verbally – or musically.

Implicit memory is sometimes called procedural because it is the memory for how to do something – how to ride a bike, how to play the piano. We acquire implicit memory through repetition and practice, and once we have learned, the memory is so deeply embedded, we don’t forget. In fact, we usually don’t remember the learning process. I doubt that many of us recall the struggles we had learning to play our instrument. And while we certainly know how to tie our shoes and do so without thinking, if we are asked to explain the process to someone, we have difficulty. We can demonstrate easily because it’s a procedural memory, but explaining would be a challenge.

Implicit memory allows us to play our instrument. Explicit memory allows us to play a specific piece of music.

But explicit memory can also be divided into two kinds – semantic and episodic, and it takes both to memorize a piece of music. Semantic memory refers to factual knowledge. While our earliest knowledge of music is about pitches and rhythms, as we become more advanced, we add all kinds of theoretical, historical, and musical information to the complex framework that constitutes our semantic memory. And that is what we draw upon as we learn a specific piece of music.

Semantic memory is knowing. Episodic memory is remembering – an important event, a movie, a particular piece of music. If we think about college commencement, we see the location in our mind, we hear the music that was played, we think about friends and family who were there, we can feel what it was like to walk across the stage to receive the degree, we may even conjure up the smells of the wonderful dinner we had. We can run the day more or less chronologically in our minds. (Of course, mine is so long ago, the chronology has become a bit fuzzy.)

With music, memory obviously can’t be “more or less” chronological. Just as in our commencement memory – visual, auditory, motor, and cognitive elements are connected together in the brain to form various episodes in the music. But with music, episodic memory is associated with the exact serial order of events, with how the piece unfolds through time. We can remember many different sections, or episodes, in the music and those episodes in serial order form the explicit memory of the piece – the memory that we are using when performing.

We obviously don’t learn – or memorize – entire pieces at once. Going back to the idea of expanding STM through chunking, it becomes apparent that we learn/memorize music in chunks. A beginner may initially read individual pitches in a melody, but once he sees that the five pitches are a 5-finger pattern, that becomes a chunk instead of 5 individual units of STM, and it’s easier to learn and memorize.

If you are at a technical level to be able to play the Beethoven Waldstein, then you don’t have to read each of the opening C major chords separately as individual units, each one occupying one of the 7 (+ or -2) units in STM. You see a much larger chunk of 7 beats leading to another chunk of 2 bars of G major chords. ( “Chunk” and “chunking” are such clunky terms to be applying to music, but sorry to say, I can’t change the accepted terminology. )

As you learn the piece, you combine smaller chunks into increasingly larger ones: phrases, sections, the exposition, the exposition plus development, eventually the entire movement. Not everyone will encode the elements of a piece in the same way. There are no right or wrong chunks, although musically, some chunks make a lot more sense than others and help to reinforce learning.

Chunking by the bar won’t be as conducive to learning the piece as will chunking harmonically, rhythmically, and melodically. But the way any two pianists “chunk” a piece of music won’t necessarily be the same. And I don’t know any pianist who would sit down and say: “OK, I am going to learn this chunk , and then that one.” It’s a more intuitive process. We look for patterns, relationships, harmonic progressions, rhythmic motifs. We don’t think “chunks,” although in brain terminology, that’s what they are.

In the excerpt from the Bach Italian Concerto below, one pianist may see the octave F interval and subsequent scalar passage to C as one chunk (outlines an F major scale plus a 5th), while another may see the following chords leading back to F as part of that same chunk. One may analyze the chords in the first two bars of the L.H. and think of them as one harmonic progression, another may be more attuned to the tenor line in those same two bars as a melody “chunk.”

But how we learn all those chunks of a piece, how we link them together, and how we encode them in our brains determines how successful we will be when we sit down to perform the piece from memory.

So next time we’re going to talk about how the neural pathways for music are formed in the brain when we learn/memorize – how the encoding of musical information actually happens. And then in the following post, we’ll look at some ways to learn/memorize so that we can be sure that all of these “episodes” in the piece are firmly linked in our brain so that our explicit memory of the piece will unfold securely over time as we are performing.

8 responses to “The many kinds of memory in music”

I miss the name of Salvador Dali in the whole article

Hi Frank, I think Dali is in a category all by himself.

Very interesting article. Thank you.

Thanks, Jenny.

Very interesting. I play piano with music. I have had a great deal of difficulty learning pieces from memory even short pieces such as Rachmaninoff’s 18th Variation on a Theme of Paganini. Simple piece once I have the music in front of me. Is this a common thing for many musicians or is it a flaw with my memories ability to store the information? I would welcome any suggestions if possible.

Hi Ken, You aren’t alone. A lot of people have problems memorizing music. There will be one or two more posts in this series on memory in addition to the three that are already posted, and I think you will find suggestions there. I don’t think it’s a flaw, I think it has more to do with how one organizes the musical information during the learning process.

Frank & Lois,

you might have come across this one from Dalí

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Persistence_of_Memory

hence the title…

Thanks. Yes, I know it well.